George Widener American, b. 1962

“Functional MRI have shown that my brain is wired slightly differently; it seems to have unusual activity that results in some innate math, memory, and drawing skills. I’ve calculated dates and specific number systems since I was a child. I’d see common numbers around me (a license plate, a house number) and immediately transform them into dates,” remembers George Widener about his early experience as an odd and gifted child. Widener was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, and although he had an outstanding ability with numbers, his childhood was marked by awkward social behavior. At eighteen he enlisted in the U.S. Air Force, where he worked as a technician for four years and then did some college coursework in mechanical engineering until mental breakdowns and financial difficulties caused him to drop out. Around this time, he became obsessed with historical dates and automatic memory drawing and focused solely on creating a counting system that he documented in notebooks, making drawings for more than a decade before anyone saw them. For a time he slept in shelters and worked in the library on his project during the day, and then decided to travel the world on a very limited budget, visiting more than seventy countries. In the late 1990s Widener was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome and enrolled in a Tennessee State vocational rehabilitation program, where he was discovered and introduced to the art world.

Widener uses found and pieced paper or a support composed of layers of tea-stained paper napkins to create mixed-media works with bold color palettes and intricate patterning. His innate ability in drawing materializes in conjunction with his preoccupation with the space/time continuum, possible numerical systems, and mind games based on historical events and dates. The sinking of the Titanic has been a fixation since he discovered that a George D. Widener from Philadelphia and his son died on the ship. “The subject of my work is that of time and, more precisely, the shifting and symmetry of time—which I believe occupy every individual’s subconscious,” says the artist, adding: “I believe that truths are often revealed in unexpected divergent events, the past and the future are joined in subtle ways. I’ve been interested in disasters as an anthropology project of sorts.” Lately, Widener has been exploring the concept of magic squares (grids of integers in which all rows and columns add up to an identical sum) to create “magic time squares” where integers are replaced with dates that not only add up to an identical sum but reflect a common theme. “For example, I might fit natural disasters to the above magic square and find hurricanes that not only fit the integers but also occurred on Fridays,” says Widener. The resulting “Magic Circles” series reflects Widener’s interest in the future development of artificial intelligence, looking forward to a future when machines will become a new species with higher creative intelligence and humans will be enhanced with skills that seem improbable today. The magic circles would thus be a form of recreation, allowing the user to “program” them by choosing a specific theme and then fitting the provided days of the week with appropriate dates, creating “crossdate” or “crosstime” puzzles.

Widener is today highly visible in the contemporary art arena and has had significant film and media exposure: he was a subject in the documentary film My Brilliant Brain: Accidental Genius (2007) and was profiled in the last episode of Ingenious Minds, a six-part series of films focusing on savants and geniuses, which aired on the Discovery Science Channel (2011). His work has been exhibited extensively worldwide, including Hiding Places: Memory in the Arts (John Michael Kohler Arts Center, 2011), The Alternative Guide to the Universe (Hayward Gallery, London 2012), and Secret Universe (Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin 2013). His work is in the collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington, D.C.), the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the High Museum of Art (Atlanta), the American Folk Art Museum (New York), the Collection de l’Art Brut (Lausanne, Switzerland), the Kröller-Müller Museum (Otterlo, Netherlands), the Treger Saint Silvestre Collection (São João da Madeira, Portugal), the abcd Collection (Paris), and the Hamburger Bahnhof National Museum (Berlin).

-

Self Portrait, 2019

Self Portrait, 2019 -

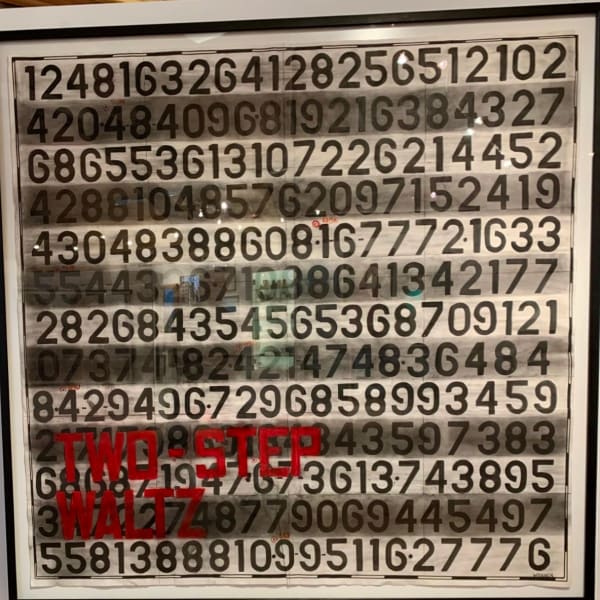

Two Step Waltz, 2019

Two Step Waltz, 2019 -

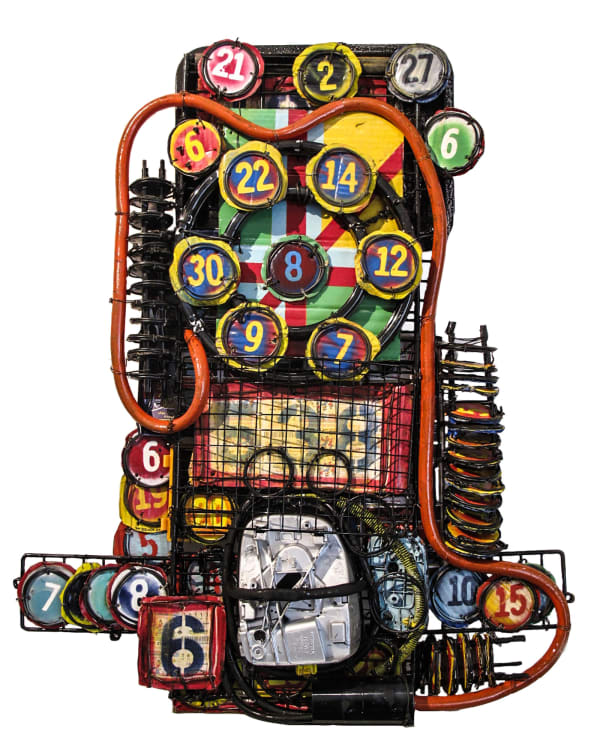

Magic Circles, 2017

Magic Circles, 2017 -

Untitled (with 6666), 2016

Untitled (with 6666), 2016 -

Work in 8 parts (8 of 8), 2016

Work in 8 parts (8 of 8), 2016 -

CRISPR No. 2, 2015

CRISPR No. 2, 2015 -

Harvest, 2014

Harvest, 2014 -

Robot Teaching Game, 2014

Robot Teaching Game, 2014 -

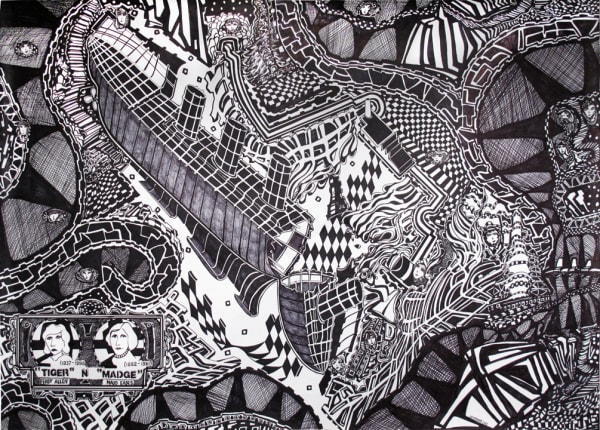

"TIGER" N "MADGE", 2013

"TIGER" N "MADGE", 2013 -

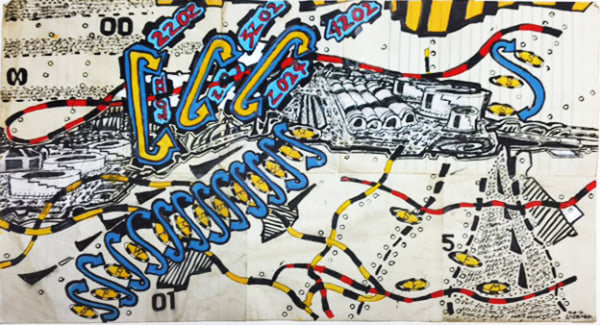

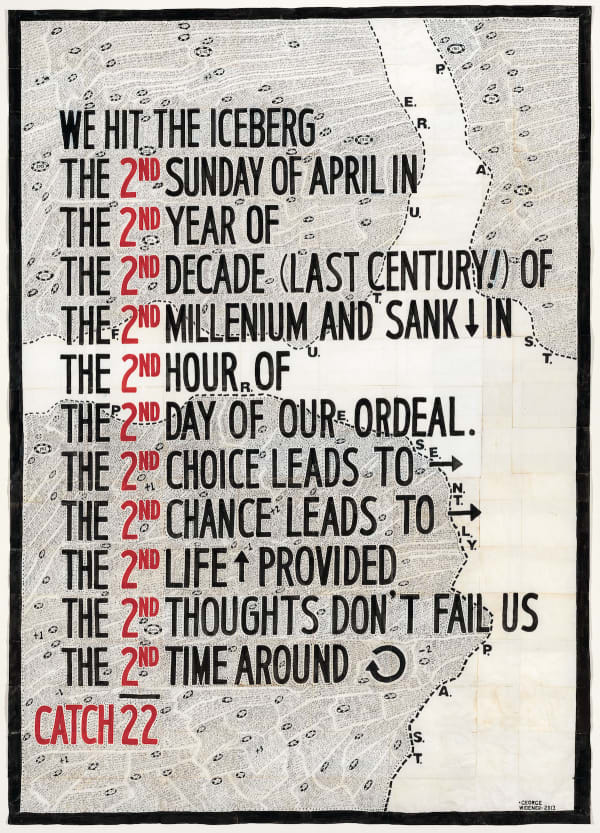

CATCH 22, 2013

CATCH 22, 2013 -

Cipher Dates, 2013

Cipher Dates, 2013 -

Untitled (Boat), 2013

Untitled (Boat), 2013 -

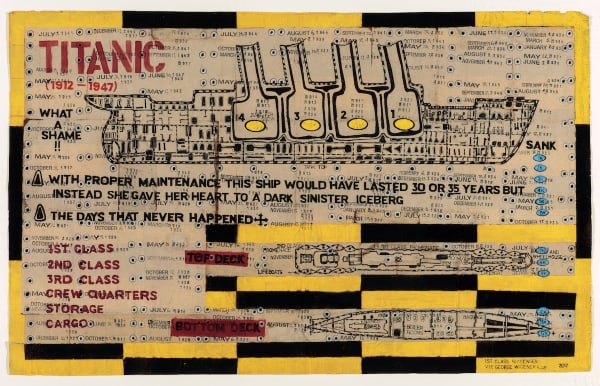

TITANIC (1912-1947), 2012

TITANIC (1912-1947), 2012 -

Titanic, 100 Years, 1912-2012, 2012

Titanic, 100 Years, 1912-2012, 2012 -

Untitled, 2012

Untitled, 2012 -

Untitled, 2012

Untitled, 2012 -

Magic Square 34, 2011

Magic Square 34, 2011 -

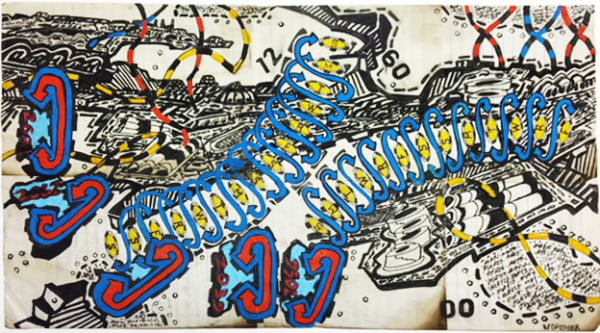

Megalopolis 789, 2011

Megalopolis 789, 2011 -

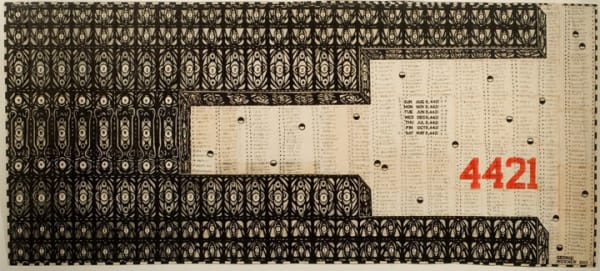

4421, 2010

4421, 2010 -

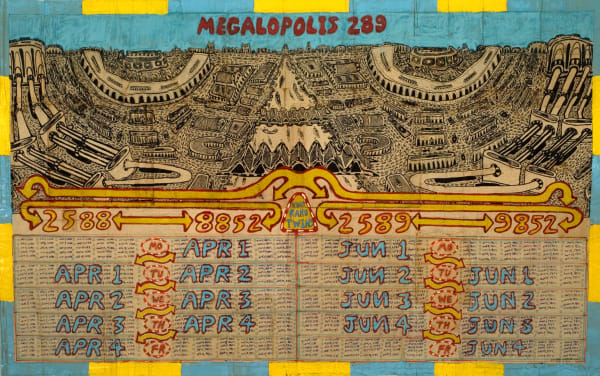

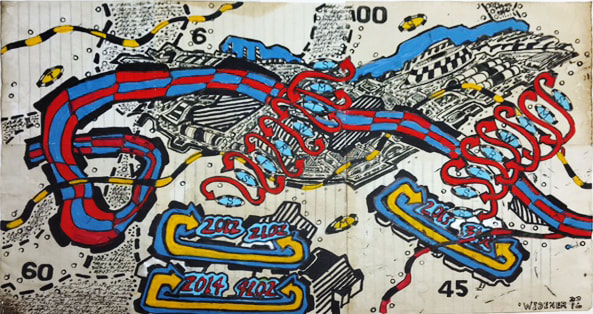

Megalopolis 289, 2010

Megalopolis 289, 2010 -

Robot Teaching Calendar, 2009

Robot Teaching Calendar, 2009 -

To Victor (two sides), 2008

To Victor (two sides), 2008 -

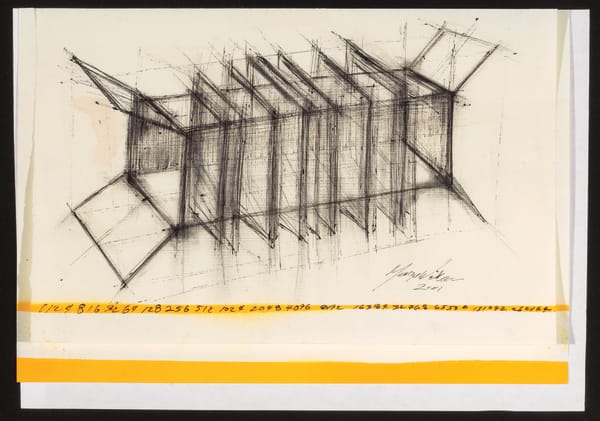

Untitled, 2001

Untitled, 2001 -

Untitled (city view) - (file card “CD”), 2001

Untitled (city view) - (file card “CD”), 2001 -

Untitled (city view) - (file card “G”), 2001

Untitled (city view) - (file card “G”), 2001 -

Untitled (city view) - (file card “IJ”), 2001

Untitled (city view) - (file card “IJ”), 2001 -

Untitled (city view) - (file card “OP”), 2001

Untitled (city view) - (file card “OP”), 2001 -

Asian Landscape

Asian Landscape -

Boat 3D

Boat 3D -

City Scene

City Scene -

Games 23

Games 23 -

Untitled (Head)

Untitled (Head) -

Work in 8 parts (1 of 8)

Work in 8 parts (1 of 8) -

Work in 8 parts (3 of 8)

Work in 8 parts (3 of 8) -

Work in 8 parts (4 of 8)

Work in 8 parts (4 of 8) -

Work in 8 parts (5 of 8)

Work in 8 parts (5 of 8) -

Work in 8 parts (6 of 8)

Work in 8 parts (6 of 8) -

Work in 8 parts (7 of 8)

Work in 8 parts (7 of 8) -

Worki in 8 parts (2 of 8)

Worki in 8 parts (2 of 8)